client and server:

In the typical use of the internet, your browser (client) makes an HTTP request to a listening program (server). The server interprets the commands, communicates with databases or other outside assistance if necessary, and sends a response that includes a status code and data. Servers can run on purpose-built servers, software or containerised computers or managed cloud offerings. Servers are designed for high availability and can perform multiple tasks simultaneously; additionally, they can operate continuously while scaling to meet increased demand for security purposes. In the typical use of the internet, your browser (client) makes an HTTP request to a listening program (server).

The server interprets the commands, communicates with databases or other outside assistance if necessary, and sends a response that includes a status code and data. Servers can run on purpose-built servers, software or containerised computers or managed cloud offerings. Servers are designed for high availability and can perform multiple tasks simultaneously; additionally, they can operate continuously while scaling to meet increased demand for security purposes.

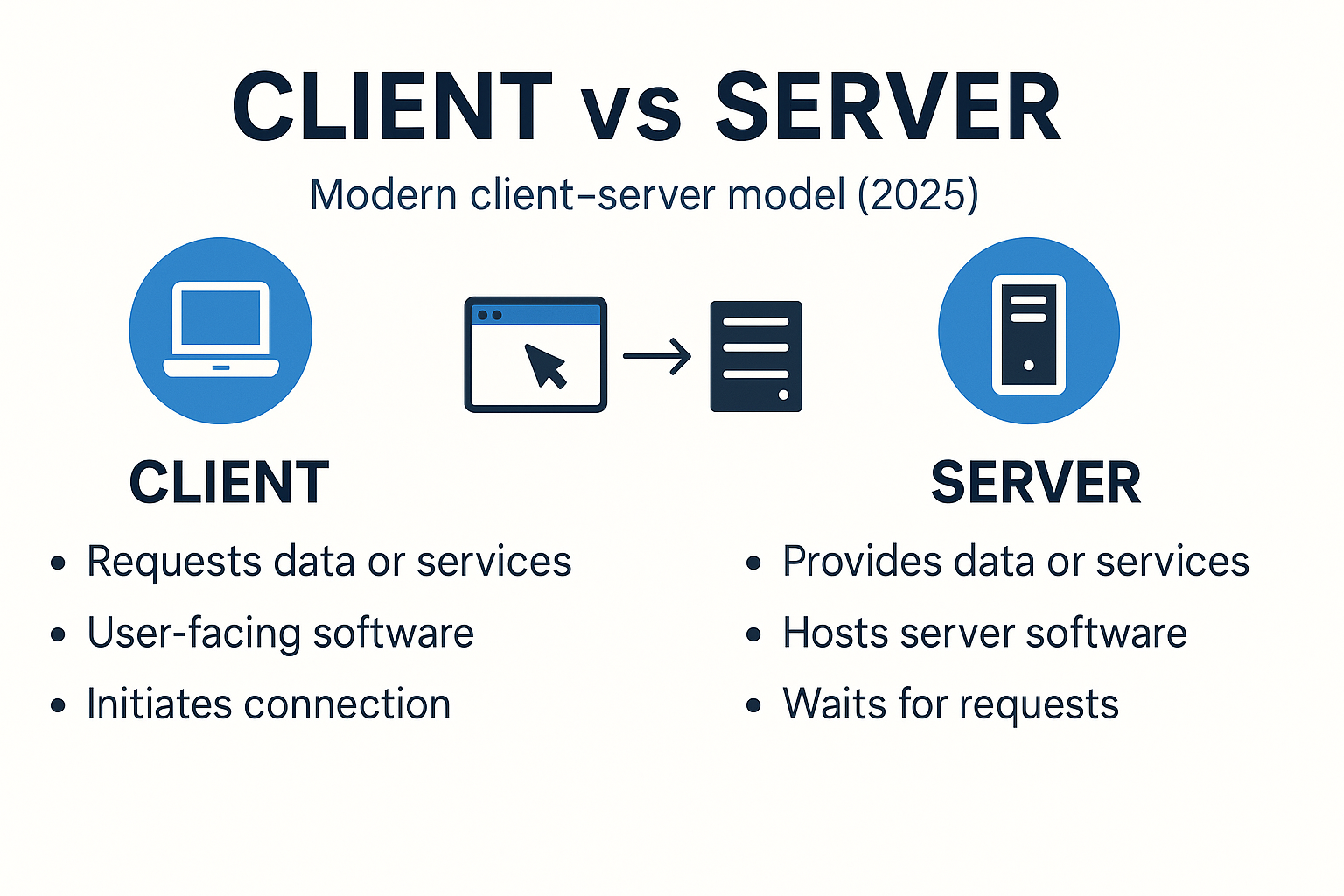

What is real meaning of server and client computer?

- Client: The requester—an app, browser, device, or service that initiates a request for data or work.

- Server: The responder—software (and the machine hosting it) that listens for requests and ful fills them.

Client server network vs Peer-to-Peer P2P

- Client–server: Centralized authority. Servers hold the source of truth, enforce security, and coordinate access. Great for websites, SaaS apps, banking, commerce, and anything requiring consistent policy and auditing.

- Peer-to-peer (P2P): Devices act as both clients and servers, sharing resources among equals. Good for decentralized file distribution or mesh scenarios where no single authority is preferred.

Why it matters: Client–server emphasizes control, compliance, and predictable performance; Peer-to-Peer (P2P) emphasizes decentralization and resilience without a single owner.

The Request–Response Journey (2025 Edition)

A simplified flow looks like this:

- Initiation – The client opens or reuses a secure connection and sends a request. Modern HTTP prefers persistent connections so each file or API call doesn’t pay the full cost of reconnecting.

- Transit – The request may pass through a reverse proxy, load balancer, or content delivery network (CDN). These layers cache content, enforce security rules, route traffic, and protect the origin.

- Processing – The origin server (or a set of services) runs business logic, queries databases, calls internal APIs, or publishes messages to queues. Cache layers may be checked first to avoid recalculating work.

- Response – The server sends a status code and data (HTML, JSON, images, video segments, etc.). The client renders or uses it and may cache it per defined rules (headers like Cache-Control and ETag).

What’s new in 2025:

- HTTP/3 over QUIC reduces head-of-line blocking and performs better on mobile and high-latency networks.

- TLS 1.3 makes secure handshakes faster and simpler, which helps both performance and security.

Clear, Practical Differences, client and server difference

| Aspect | Client | Server |

|---|---|---|

| Core role | Initiates requests; presents results to a human or another system | Listens for requests; processes and returns results |

| Typical home | Browser, mobile app, desktop app, IoT device, or another service | Data center, cloud VM/container, on-prem hardware, or edge location |

| Lifecycle | Starts/stops frequently; user-driven | Long-lived; built for uptime, monitoring, rolling updates |

| Resource profile | UI/UX, local cache, modest compute | Heavy compute, storage, concurrency, strict security |

| Trust & identity | Verifies the server identity (certificates) | Authenticates clients; enforces authorization and rate limits |

| Scaling | More users → more clients appear organically | Scale up (bigger instance) or out (more instances) behind a load balancer |

What the Client Actually Does

Modern clients do more than “click and wait.” They:

- Reuse connections (keep-alive) to avoid repeated handshakes.

- Cache responses based on headers and conditions.

- Retry intelligently on transient failures and back off when rate-limited.

- Prefer secure defaults (HTTPS, certificate validation, content security policies) to protect users.

- Use streaming or real-time protocols when appropriate (WebSockets, SSE, or APIs that support streaming responses).

- Optimize for power and bandwidth on mobile devices.

A Banking Login: End-to-End Example

- You open the bank’s app and tap Log in.

- The client establishes a secure connection (TLS 1.3).

- A reverse proxy or CDN at the edge terminates TLS, screens for suspicious patterns, and forwards the request to the application layer when needed.

- The application server validates credentials—often calling an auth service—and then queries accounts and balances from a database server.

- The response returns through the same path. The app renders your dashboard and may keep the connection alive for subsequent API calls.

- Static assets (images, scripts) are cached at the edge to reduce latency. Critical data is fetched fresh from the API with proper authorization on each call.

Protocols That Matter in 2025

HTTP/1.1 → HTTP/2 → HTTP/3 (QUIC)

- HTTP/1.1 improved on early HTTP with persistent connections, but each connection effectively served one request at a time.

- HTTP/2 brought multiplexing: many concurrent streams on one connection, plus header compression. This benefits API calls and asset delivery.

- HTTP/3 runs over QUIC (built on UDP) and avoids certain TCP bottlenecks. It tends to perform better on lossy or mobile networks, and adoption has widened across browsers and edge networks.

TLS 1.3

TLS 1.3 simplifies the handshake, trims legacy algorithms, and often completes the setup in fewer round trips. It’s both faster and safer compared to older versions.

WebSockets

For scenarios like chat, collaborative editing, trading dashboards, or multiplayer games, WebSockets allow a single, long-lived, full-duplex channel. The server can push updates as they happen, and the client can respond instantly.

gRPC

gRPC is commonly used for service-to-service communication in microservice environments. It rides on HTTP/2, offers streaming, and uses strongly typed contracts defined with protobuf. It’s not required for every system, but it’s a good fit where speed, schemas, and inter-service streaming matter.

Reverse Proxies, Load Balancers, and API Gateways

These are sometimes confused, and products may combine features, but it helps to separate the concepts:

- Reverse proxy: Sits in front of your origin. Terminates TLS, caches responses, compresses payloads, adds/remove headers, filters requests, and forwards them to the proper backend. It can block obvious threats and offload expensive work from the origin.

- Load balancer: Distributes traffic across multiple backend instances. This can happen at Layer 4 (transport) or Layer 7 (application), improving throughput and availability.

- API gateway: Centralizes cross-cutting concerns for APIs—authentication, rate limiting, request validation, routing, and observability—and simplifies client integration in a microservices setup.

2025 Realities That Shape Design Choices

1) Edge and CDN-Backed Delivery

CDNs replicate content worldwide so users fetch from nearby locations. Edge compute executes lightweight logic—header manipulation, A/B targeting, bot mitigation, and shallow personalization—without a full trip to the origin. This reduces latency, saves bandwidth, and protects core services.

Good uses: Static assets, cacheable API responses, geo-based routing, feature flags, canary logic, and pre-authentication checks.

2) Serverless and Managed Runtimes

With serverless, providers manage the fleet. You write functions or minimal services; the platform auto-scales, patches, and bills per usage. The client–server model remains, but much of the “server care and feeding” disappears.

Strengths: Bursty workloads, event-driven tasks, scheduled jobs, cost visibility for sporadic traffic.

Considerations: Cold starts are smaller than before but still exist; tracing across many functions can be tricky without good tooling; architectural sprawl is easy if boundaries aren’t clear.

3) Secure-by-Default Protocol Stack

Widespread availability of TLS 1.3 and HTTP/3 makes it realistic to default to fast, encrypted connections virtually everywhere, and to gain resilience on less reliable networks.

Architecture Patterns: Picking What Fits

Monolith Behind a Reverse Proxy

Use when: Team is small, product is young, and features are changing fast.

How it works: A single application handles web pages and APIs. A reverse proxy terminates TLS, adds caching and compression, and routes traffic to the app.

Benefits: Simple codebase and deployment.

Watch-outs: As the codebase grows, deploys can become slower, and boundaries between domains can blur.

Microservices with an API Gateway

Use when: Multiple teams need to ship independently and scale different features at different rates.

How it works: Many small services communicate via REST or gRPC. An API gateway enforces authentication and rate limits, and provides a single entry point for clients.

Benefits: Independent scaling, clear domain ownership, smaller deploy units.

Watch-outs: Network complexity, distributed tracing, and eventual consistency across services.

Serverless + Edge Mix

Use when: Global audience, spiky traffic, and minimal ops overhead are priorities.

How it works: Static assets and lightweight logic run at the edge; serverless functions implement APIs; managed databases handle persistence; background tasks run as scheduled functions or event consumers.

Benefits: Automatic scaling, reduced ops work, lower latency.

Watch-outs: Observability and cost predictability require attention; ensure clear boundaries between edge logic and core business rules.

Performance Essentials (Client and Server)

Client-side

- Reuse connections with keep-alive and prefer HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 when available.

- Use caching directives and conditional requests to avoid unnecessary downloads.

- Choose real-time transports wisely: WebSockets or streaming endpoints beat frequent polling.

- Defer non-critical work (lazy-load assets, prefetch prudently).

Server-side

- Terminate TLS with TLS 1.3; enable modern ciphers and ALPN for HTTP/2/3.

- Place a reverse proxy or CDN in front of origins; compress text assets; leverage caching for static and idempotent content.

- Keep services as stateless as possible; store sessions in shared stores when needed.

- Use connection pooling for downstream resources (databases, other services).

- Monitor p95/p99 latencies, error rates, saturation, and cache hit ratios.

Security Essentials (Without the Jargon)

- Encrypt in transit: HTTPS everywhere with modern TLS.

- Know who’s calling: Use standardized authentication for users (for example, tokens from an identity provider) and strong credential practices for services (mutual TLS or signed tokens).

- Limit what’s allowed: Role-based or attribute-based authorization, enforced on the server.

- Validate inputs and encode outputs: Prevent injections and cross-site scripting with rigorous validation and safe rendering patterns.

- Rate-limit and filter at the edge: Stop abusive traffic before it reaches the origin.

- Protect secrets: Use managed secret storage; rotate keys and credentials regularly.

- Least privilege: Grant only the minimum permissions needed for each component.

Reliability and Scaling

- Redundancy: Run multiple instances across zones or regions; use health checks and automatic failover.

- Load balancing: Evenly distribute incoming requests; keep sticky sessions to a minimum or move session data out of the instance.

- Graceful degradation: If a downstream dependency is struggling, show partial results or cached content rather than failing completely.

- Backpressure and timeouts: Don’t let one slow dependency stall the whole system; apply reasonable timeouts and circuit breakers.

- Disaster recovery: Snapshot data, replicate critical stores, and rehearse failover scenarios.

Data Management in client and server Systems

- Databases: Choose between relational (transactions, strong constraints) and non-relational (flexibility, horizontal scale) stores based on access patterns.

- Indices and queries: Good indexing matters more than adding CPU. Measure real queries and optimize hot paths.

- Caching tiers: Database query results and rendered fragments can be cached at the application level and at the edge.

- Consistency: Understand the difference between read-after-write consistency (often required for user-visible data) and eventual consistency (suitable for analytics, counters, or feeds).

- Backups and retention: Define recovery point objectives (how much data you can lose) and recovery time objectives (how fast you must restore).

Cost and Efficiency

- Right-size instances: Overprovisioning is wasteful; underprovisioning causes errors and slowdowns.

- Autoscaling: Scale out during peaks and back in during lulls; monitor to avoid thrashing.

- Cache to save: Caches and CDNs reduce origin load and bandwidth costs.

- Observe data transfer: Egress charges can dominate bills for media-heavy apps.

- Batch and queue: Background tasks and queues smooth traffic spikes and let you buy smaller capacity with fewer emergencies.

Real-World Examples (Mapped Clearly)

- Web browsing

Client: your browser. Servers: edge/CDN nodes plus origin web and application servers. Static assets are cached near you; dynamic data comes from APIs behind the proxy. - Email

Client: a mail app. Servers: SMTP for sending, IMAP/POP for retrieval, plus filtering and storage layers. - Online banking

Client: mobile or web app. Servers: reverse proxy, authentication service, API services for accounts and transactions, database clusters replicating across zones. - Streaming video

Client: TV app or mobile app. Servers: origin packagers, CDN edges serving segmented media files, license servers for DRM, analytics pipelines for quality and engagement. - Online gaming

Client: console or PC. Servers: authoritative game servers for state and physics; real-time channels for chat and events; matchmaking and profile services in the background. - IoT telemetry

Client: sensor or gateway device. Servers: ingestion endpoints that buffer and validate events, stream processors, and data lakes/warehouses for long-term analysis.

Quick Reference: Choosing the Right Approach

- Small app / MVP: Monolith plus reverse proxy/CDN. Ship quickly with a simple pipeline and grow later.

- Growing product with multiple teams: Microservices with an API gateway and centralized auth. Add a service mesh if you need advanced traffic policy internally.

- Global audience and spiky traffic: Serverless APIs, managed databases, and edge logic for latency-sensitive paths.

- Real-time features: WebSockets for live user experiences; gRPC streaming for service-to-service updates.

Conclusion

Client/server computing is a model that remains the backbone of modern computing. In 2025, the fundamentals are the same—clients initiate, servers serve—but the toolbox is richer: HTTP/3 and TLS 1.3 for faster, safer connections; reverse proxies, load balancers, and gateways for control and reliability; CDNs and edge compute to push logic closer to users; serverless to shrink operational overhead; and robust patterns like WebSockets and gRPC for real-time and service-to-service communication.

How to make a computer server?

To make a computer server, you need to install server software (e.g., Apache, Nginx, or Windows Server), configure the operating system for hosting, set up necessary services (like FTP, web, or database), and ensure proper networking through port forwarding and firewall settings.

What is the client and server difference in simple terms?

A client starts the conversation by requesting data or an action (for example, your browser). A server listens for those requests and responds with the requested data or result (for example, a website’s backend).

How to make a server in computer?

This involves selecting a purpose (e.g., web hosting, file sharing), installing a suitable server OS (like Ubuntu Server or Windows Server), and configuring roles such as HTTP, database, or DNS servers.

How to access localhost server from another computer?

To access a localhost server from another computer, ensure both devices are on the same network, find your server machine’s IP address, open the necessary ports (usually 80 or 443), and enter that IP address in the client browser.

What are common types of client and server?

Web servers (static content), application servers (business logic, APIs), database servers (data storage and queries), file/object storage, mail servers, authentication/authorization servers, cache servers, reverse proxies, and CDN/edge servers.

What are the main advantages of client and server systems?

Centralized control and security, easier compliance and auditing, straightforward backups, and scalable performance through caching, load balancing, and CDNs.

How do real-time features fit into client server network?

Real-time features use persistent connections (WebSockets) or streaming APIs so servers can push updates as they happen. The model is still client–server; the transport is just long-lived and bidirectional.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!